A Short Story of my Fellowship Year in Images: Thinking Miniatures & (Climate) Colonialism

The Big Event trade fair in Den Bosch, October 2021 and later in Utrecht, June 2022.

The miniatures fair was a boon.

I found nappies (miniature representations of reproductive labour) and Dutch cheese (trade; lekker).

In December I hosted a two-part skill-sharing and storytelling workshop with the Jewellery – Linking Bodies students, who introduced a sustainable and/or localized skill or craft practice and then told a story or anecdote that connected them to this skill. By focusing on skills and materials that are local, accessible, and anti-heroic, we attempted to humbly resist the tired story that the biggest, the most bombastic, and most expensive things are those that are “worth” the most. After all, stories bring things to life and enliven relationships.

Irma Foldenyi opened up the departmental jewelry archive, which contains work dating back to the late 1960s from the Rietveld Jewellery – Linking Bodies alumni.

Early stage of research involved a lot of seeing, looking, and talking. Pictured is Warrior amidst trophy arms pendant, Netherlands, 1590.

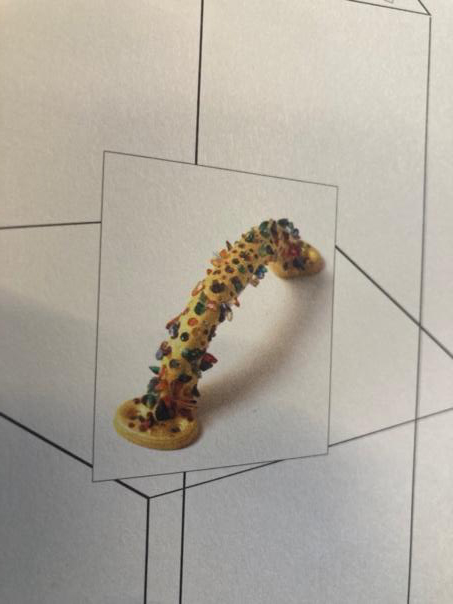

Looking at regional jewelry and miniature traditions and seeing how resources move. Pictured is a work by Karl Fritsch.

I was attracted to the Renaissance love pendants in gold, precious gems, and enamel, and their symbolism (hands, hearts, doves).

And floored by the contemporary work of Jasmine Thomas Girvan at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, whose decolonial politics, literary narrative techniques, and accounts of contested Caribbean histories invite attention using detail, scale, and found materials.

Around this time I wrote a thing about pearls and jewelry—wanting to caress the sensual, terrible, and deviant possibilities of “detail” in European art and adornment in order to work against the genre-wash of (colonial) historicization and the classification of gender, race, and sexuality.1

Pictured: Anonymous, Pedestal pendant with Amphitrite on a dolphin, circa 1730–1750.

Back in Amsterdam Zuid I encountered the solid domesticity of this public sculpture from 2018. Louise Schouwenberg looked into the artist, Matthew Darbyshire, and told me in an email that the work “refers both to an apartment next to the square and an apartment described by Georges Perec. It contains design icons from Dutch museum collections and anonymous furniture of people around the square, so many interpretations are battling here.”

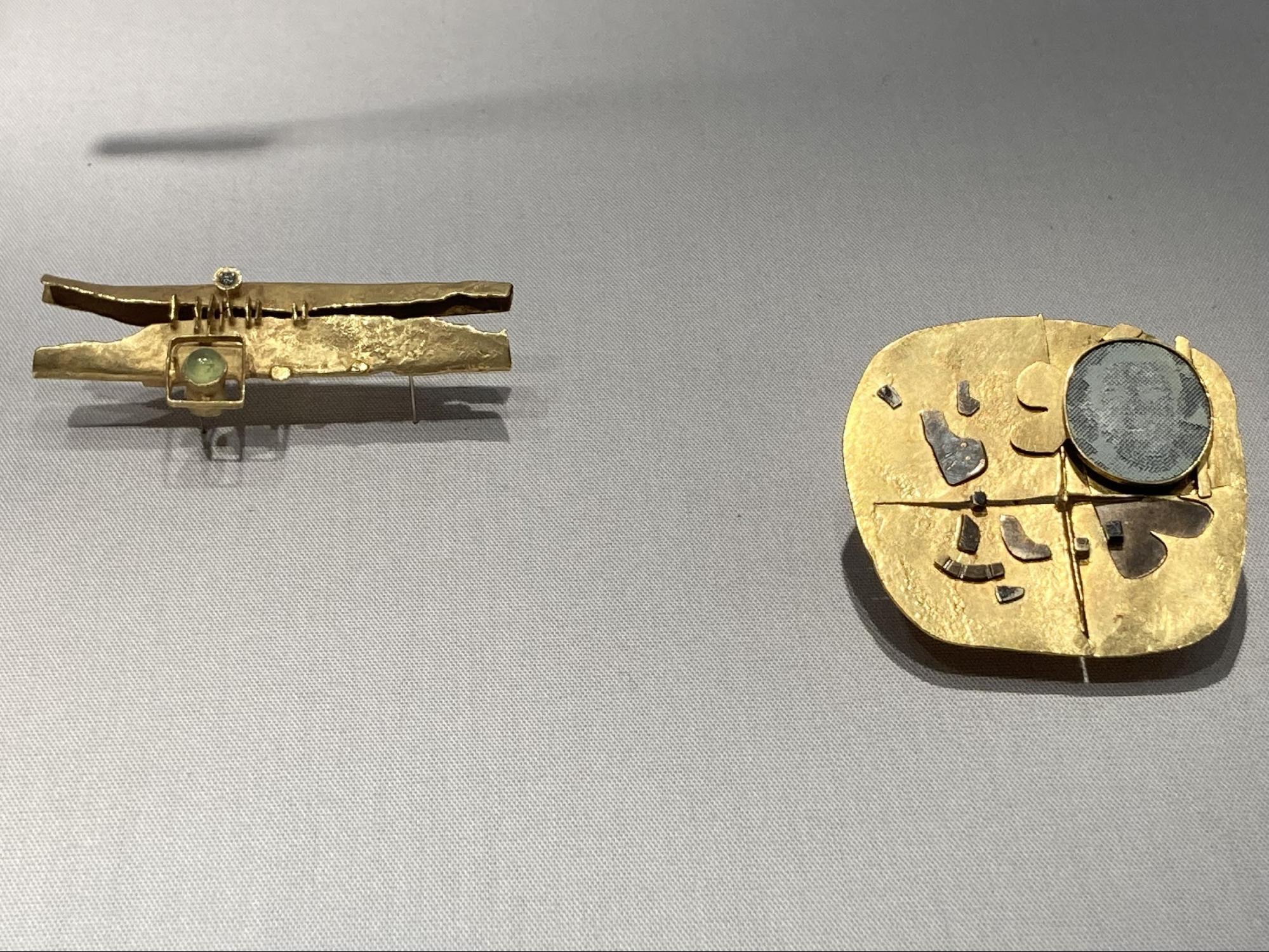

A journey to Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim in March. This art nouveau brooch (1902) is by Georges Fouquet.

These incredible modernist brooches (1959) are by local goldsmith Reinhold Reiling.

Jumana Emil Aboud’s cabinets (like) and interweaving of objects, text, and storytelling (love) at documenta fifteen.

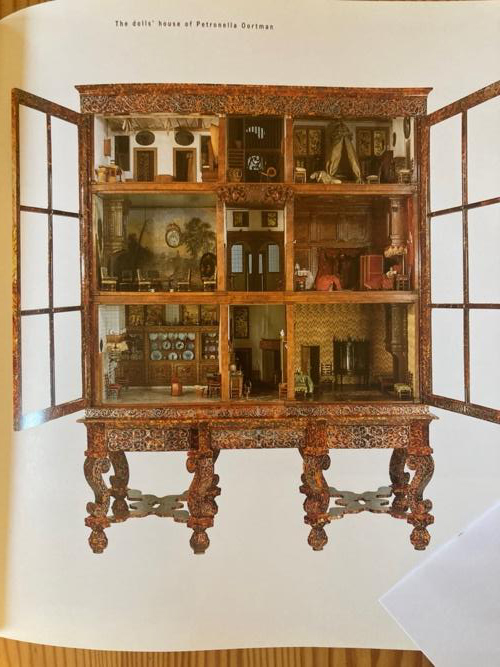

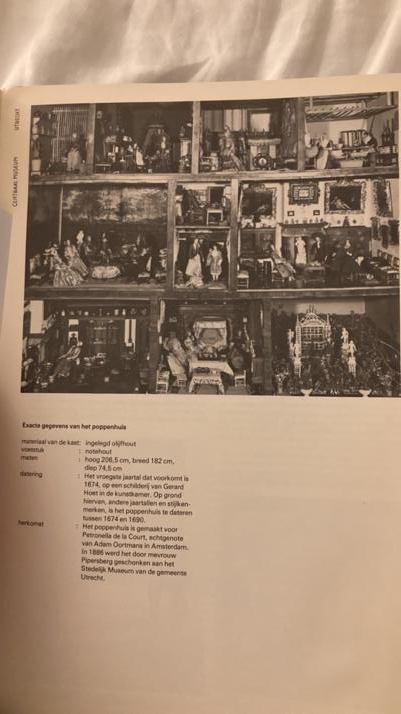

Returned to Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam to visit the Dutch dollhouses. This one pictured was commissioned by Petronella Oortman. The detail is astounding. Every element tells a material story of how European colonialism was working at the time, speaking of its universe of values and beliefs.

I bought a postcard.

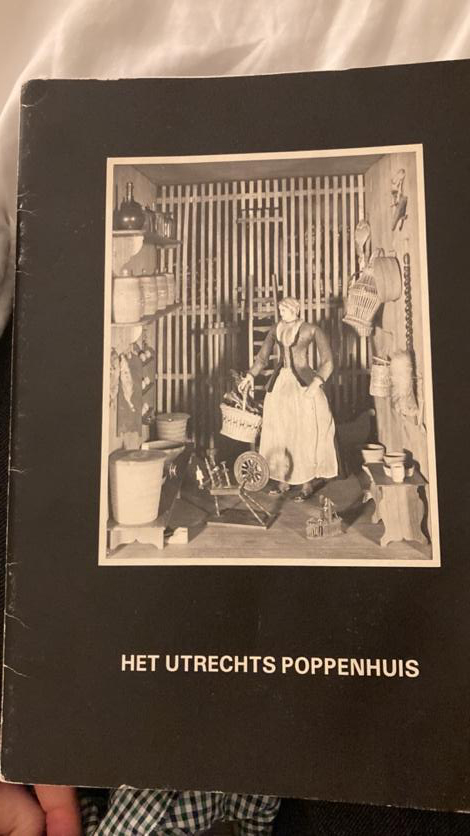

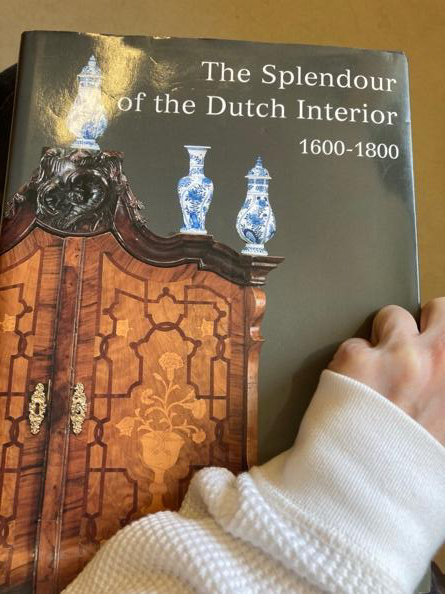

And started seeking out books on bourgeois Dutch dollhouses, like Centraal Museum’s 1972 book on Petronella de la Court’s dollhouse.

How to explode or trouble or complicate the dollhouse form? Or how might I work with the Dutch dollhouse as a formal proposition?

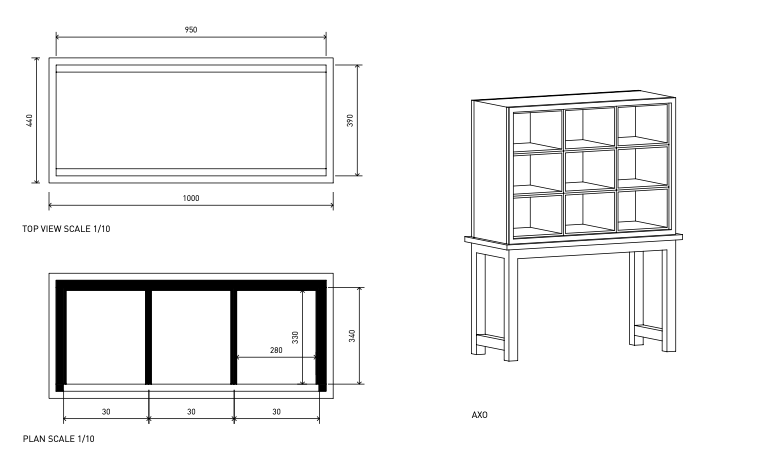

1:12 iteration of Petronella Oortman’s magisterial poppenhuis held at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Sketches by Ioana Lupascu.

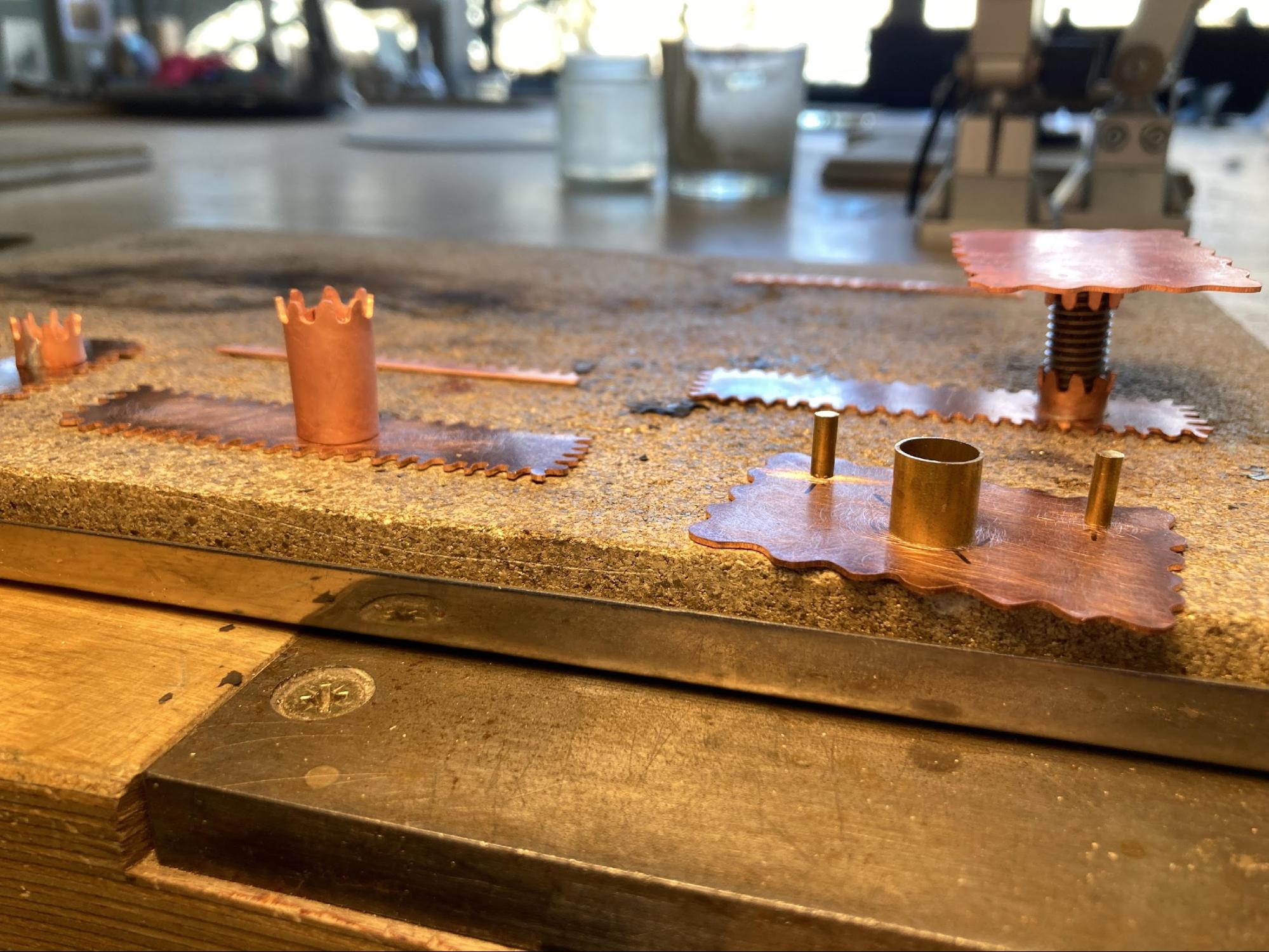

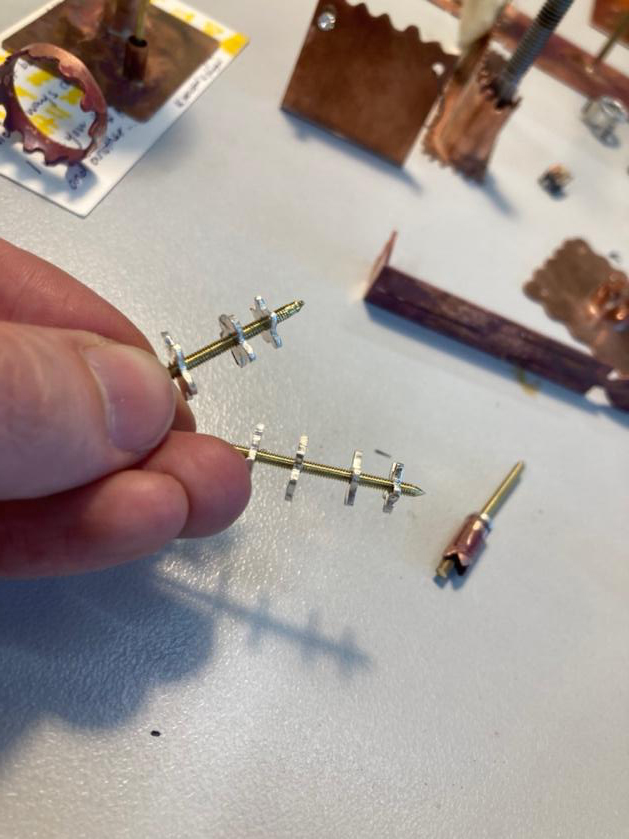

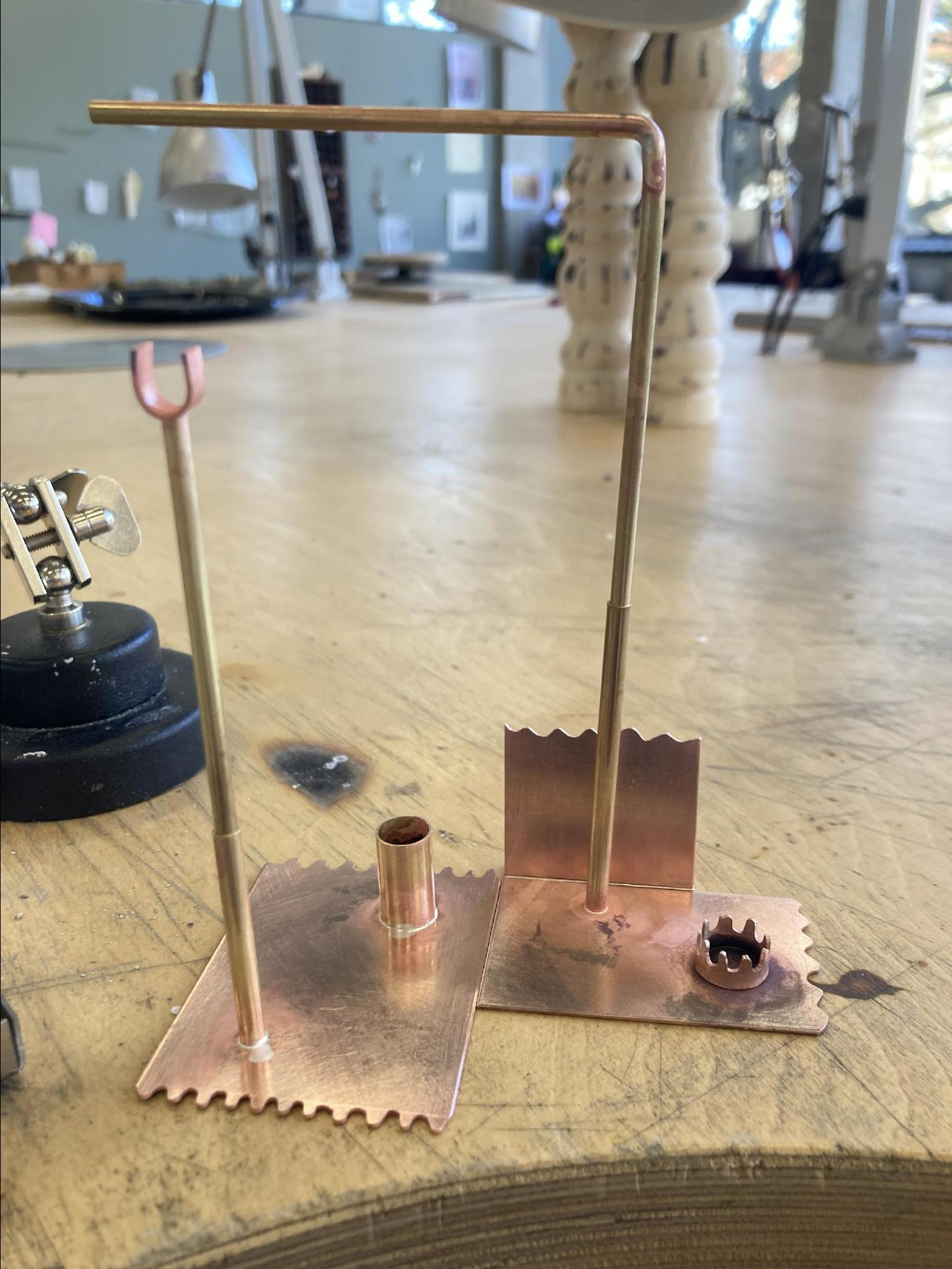

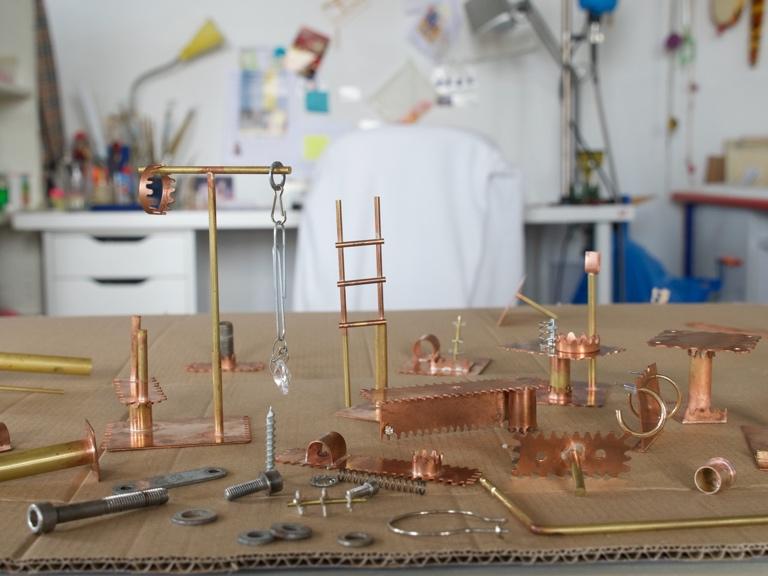

Back at the bench I play around with making. Thinking about ways that these forms and shapes could fit within a dollhouse.

Thinking also about the socializing power of imagery and how the gender lines of the nuclear family are reproduced in toys and play.

Also marveling because I have access to machinery, and technicians to learn with.

I learn sandcasting,

Practice engraving,

The lathe,

And return to threading.

But my subject and desires are too broad; I scale it all down. I’m back to my love of jewelry, the basic craft. The repetitive actions of sawing, the focus and ceremony demanded by soldering, the delight in polishing.

Thinking about artworks that click together,

Artworks that reconfigure and so refuse containment or completion.

Studio visit with Katayoun Arian, in which we rearrange together. Katayoun notices a small rice sculpture I made that is three rice-grains wide. I am energized to continue working at this even-tinier scale.

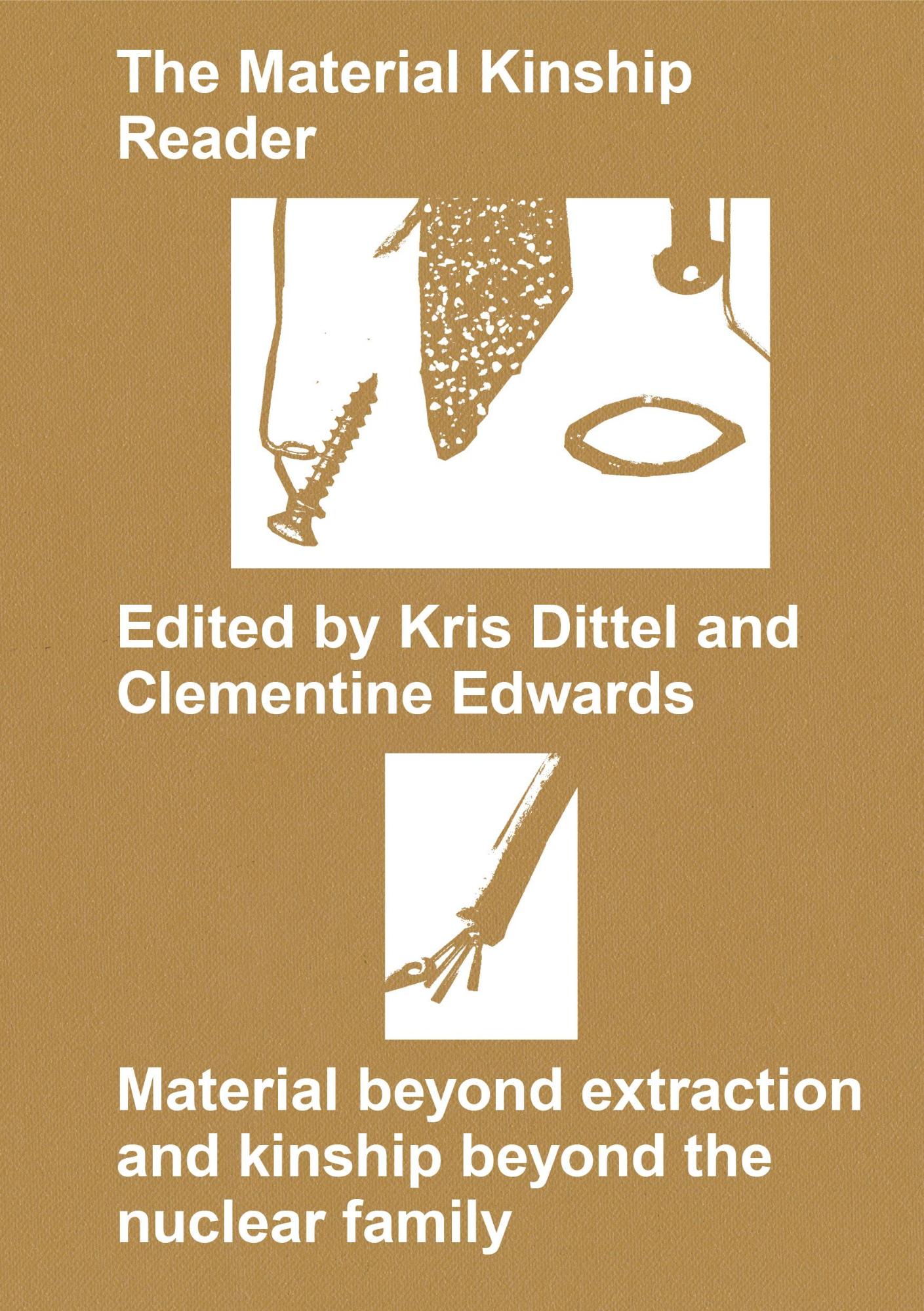

Intermission: the publication of my and Kris Dittel’s new book, The Material Kinship Reader.

I’m drawn to rice because it’s a widely accessible and recognizable material. Its cultivation has different environmental implications depending on where we are in the world but it remains a staple food for ongoing planetary survival.

Collecting things on the street.

And putting those things into conversation with what I make.

In September, I develop a passion for Dutch doorknobs, bronze and brass table mounts of the late eighteenth century, and table-leg ornamentation in general—taking inspiration from dollhouses and also thinking about things we touch and connect with, things that are functional and ornamental.

In this time I trawl second-hand bookshops, the backstreets of Delfshaven, an antique fair in Utrecht, and Het Schielandshuis—the oldest building still standing in Rotterdam—to see the boardroom with original fittings.

Mum becomes my unofficial but equally interested research assistant and sends me academic papers on knobs and latches, and the names of key Rotterdam domestic painters from the period. In a moment of delirium I think I might hand-turn sixteen doorknobs and four table legs from solid brass rod.

In the end, I sandcast a contemporary doorknob four times using scrap brass.

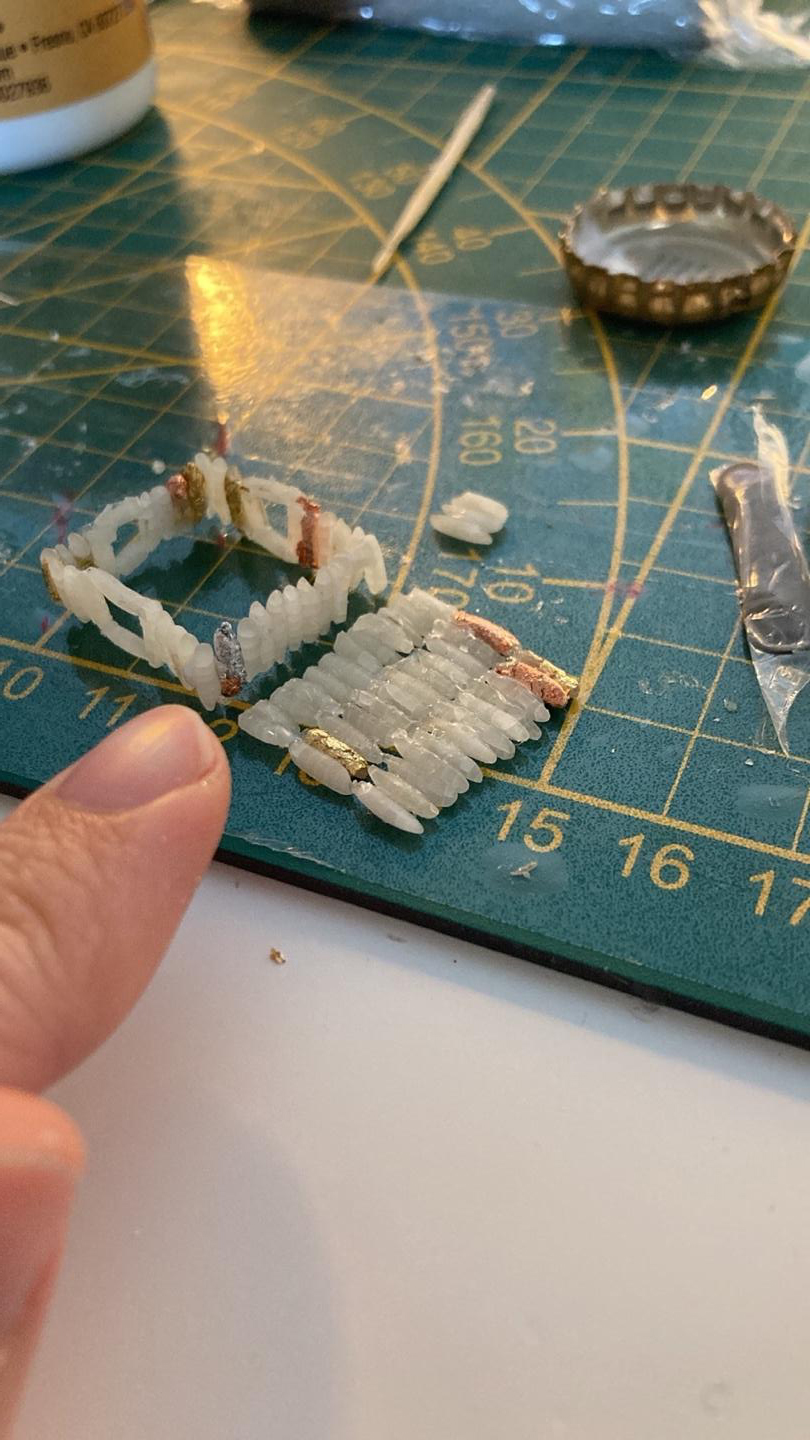

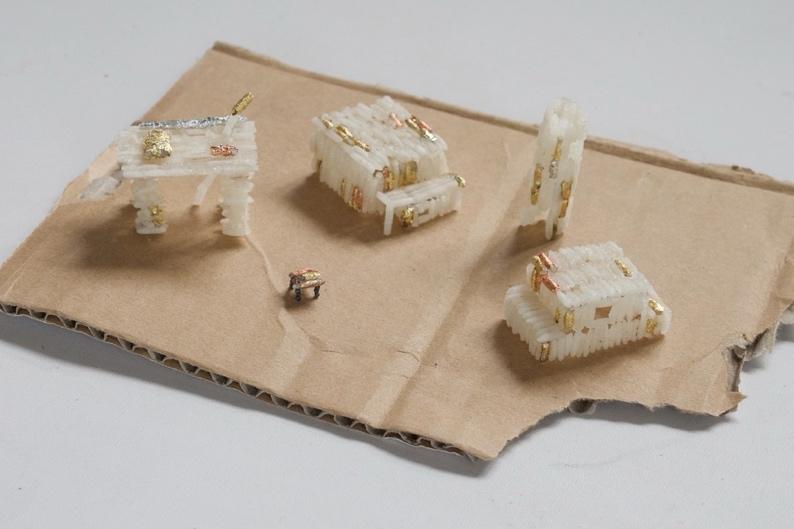

I continue experimenting with making structures using rice and gold, silver and copper leaf.

Glamour shot of a rice village.

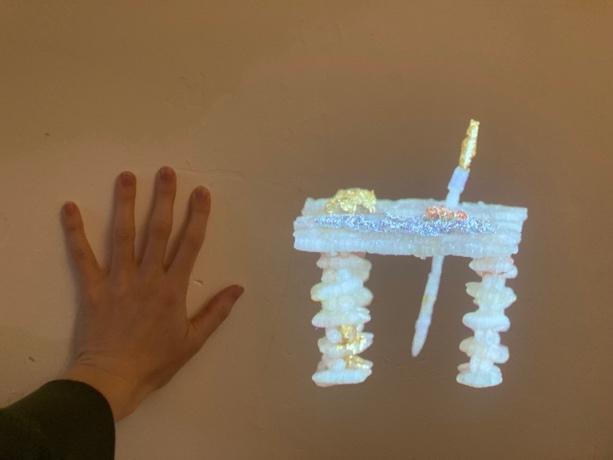

Scaling up the rice houses via projection.

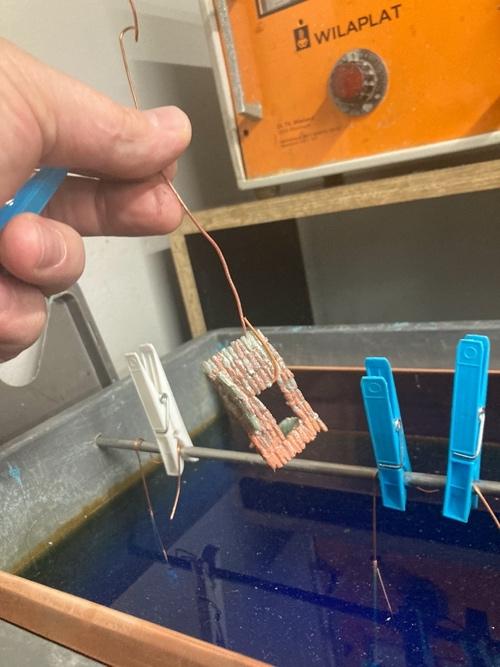

Peter Elbers teaches me to electroplate.

Pictured here are some of my failed attempts at copperplating the rice structures.

I turn to lost-wax casting.

A success: there is a wonderful weight to the 14-karat-gold rice house.

Along the way, an idea is hatching, to conjure a dollhouse in words and story. No images. Guided by the eleven-room floorplan of Petronella de la Court’s dollhouse held at Centraal Museum, Utrecht, I want to speak to eleven different art practitioners—one for each room—about queer and/or anti-colonial dollhouse possibilities. I invite them to dream into the room away from structures that inhibit. Ultimately, I want to produce a pamphlet-cum-artist book, with one spread per artist, that functions as a formal and reparative response to seventeenth-century Dutch dollhouses. I manage interviews with five artists. We each have a one-hour conversation that I record, transcribe, and then reconfigure into short texts/poems for performance. The pamphlet dream dematerializes into my fellowship presentation.

My head is spinning. I’m making now for a show at Tent Rotterdam with Katayoun.

Glamour photos of rice and copper works at the studio taken by Marta Hryniuk.

At the opening at Tent Rotterdam, 2022. Photo by Mark Bolk.

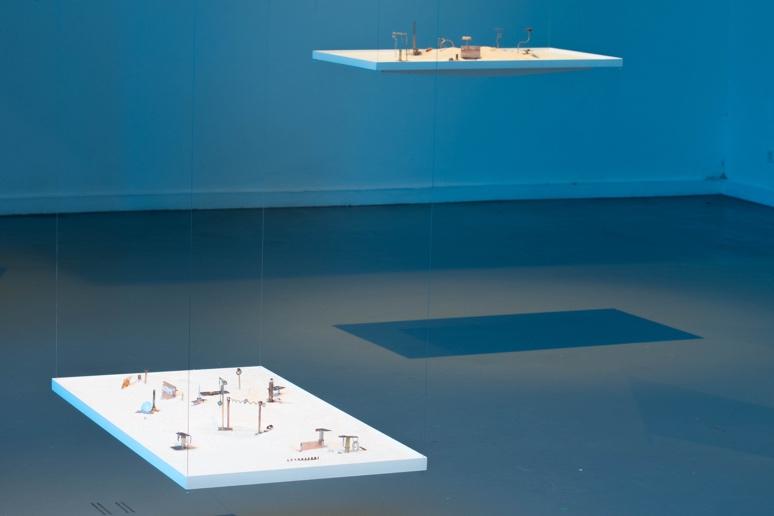

Floating platforms of the almost-endlessly reconfigurable rice and copper works. Photo: Nick Thomas.

Tiny shelf and found materials. Photo: Aad Hoogendoorn.

A minor triumph: I exhibit the micro rice work, only three rice-grains wide. Photo: Nick Thomas.

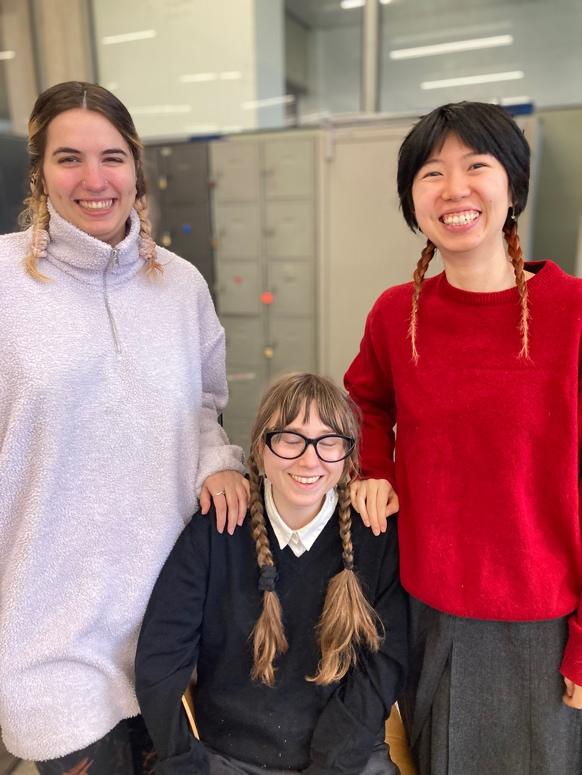

I neglected to take photos of the whole department, who welcomed me so warmly, but here is a picture of six plaits on three students: Myrthe Kamoen, Karla Nilzee, and Yawen Fu.

Thank you to Sonia Kazovsky for backing me from the get-go, Sonja Baumel for your warm commitment and generosity, Peter Elbers for your ongoing grace, the 2021–2023 students for being so very welcoming, and Liza Prins for being the fellowship wizard of it all.

1Clementine Edwards, “Rimming Pearls,” Sieradenmuze, https://www.sieradenmuze.nl/blog/rimming-pearls.